Tom Hunter has an approach to work that is both serious and considered. Rather than the veil of humour and irony that masks much of contemporary art, Hunter’s work is unashamedly artful. Moreover, his position is not solely expressed by nods to the story of art. For equally, the work is socially aware and engaged with the chronicle of our contemporary world.

Hunter inhabits a place of his own creation (much like the Travellers he pictures at times): a place between two metaphors traditionally used to explain artists: artist-as-researcher and artist-as-teacher. In Hunter’s oeuvre, there is a rare harmony to be found in the duality of nods to art history plus voiceable convictions. Each of the twin impulses are felt with harmonious gravity. In short, Hunter is not wishy-washy. He is not sitting on the fence. His ‘voice’ is as deliberate as his work is diligent. And as such, his work is crystal clear and it resonates with a broad range of the contemporary audience.

Hunter’s photography seems to refer to social policy as much as art history. “I’m re-enacting scenes from every day life,” a pragmatic Hunter offers, “which signify what’s going on around us in today’s society.” There are many examples of this impulse: images of a desolate high rise (a symbol of bungled attempts to solve the issue of housing); through the alternative housing choices made by people in Hackney; and on to the ‘Traveller’ micro-communities which could be said to be the polar opposite of government-led pipe-dreams.

Hunter’s interests may also be seen in the use of motifs made popular throughout the story of art, e.g. ‘the window’ with its symbolic and metaphoric potential to suggest an opening or a closure to the infinite cosmos beyond, i.e. ‘the sublime’ -that paradoxical sensation of insignificance in, and oneness with, our universe.

Hunter’s portraiture is serious and considered, and unashamedly artful in several complimentary senses: the committed endeavour; the technical proficiency; the allusions to historical references; the super-sleek presentation. Moreover, the shot selection and interest in the chosen subject matter -the composition and care- are evident in each frame. “I use a 5×4 camera, large format,” Hunter clarifies, “I use a tripod. I use Polaroids in the planning stage.” Moreover, Hunter suggests “My subjects are made to feel important.” All of this pays dividends in the finished article.

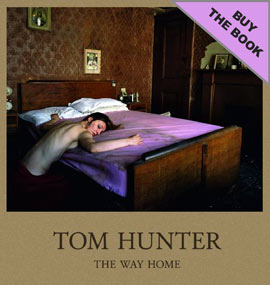

In a sense, Tom Hunter joins a rare band of true originals in the history of British portraiture. Like Gainsborough, for example, Hunter achieves a palpable -perfect?- sense of privacy and intimacy. That is, the photography reveals the coming together of two solitudes (artist & subject) who have approached, respected and protected one another … before, during and after the photograph.

Hunter’s subjects for portraiture are not the rich looking to add to their ancestral totems. They are the disenfranchised, disenchanted, or at least, the all too easily misconstrued members of society. People who themselves rightfully choose to live on the margins of mainstream society (e.g. ‘Travellers’). Despite the fact that such people are often stereotyped, Hunter often pictures these subjects alone which engenders an air of intimacy and a sense of individual worth. Hunter says of them, “I really wanted to show that the subjects I was dealing with were as important as the rich and famous people, in the same way as Vermeer.”

Indeed, amongst the art historical references glimpsed within Hunter’s oeuvre, the voyeurism of Vermeer is most discernible. Subjects are often shown full figure, in private spheres (e.g. sites of domesticity), and set in the mid-ground in order to include something of their environment. In portraiture terms, this is composition which suggests that the environment of the subjects is integral. Indeed, these spaces say something of the subjects, promoting them as the self-made, self-contained, self-governed, despite being what the mainstream may call ‘alternative lifestylers’ or worse. But of course, things are often more intriguing on the periphery. In confirmation, Hunter’s photography reveals the self-respect and self-worth of this unusual selection of subjects.

By TIM BIRCH