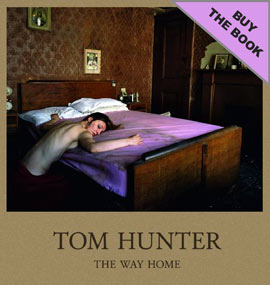

From The Ghetto to the National Gallery, Tom Hunter continues to explore themes that depict his local neighbourhood, drawing on art historical references to paint Hackney in a different light to the usual lurid newspaper stories of urban blight.

Three years ago Paul Wombell curated a group exhibition for Photo España in Madrid drawing attention to what he said was a small but growing band of photographers who were responding to the world at a local, neighbourhood level.

Arguing that they offered an important counterpoint to the “totalised view of the world” presented by the “global photography” of Andreas Gursky, Sebastião Salgado, Thomas Struth and others, the show (Local, The End of Globalisation) included work by Tom Hunter, whose commitment to and engagement with the area he had lived in for more than a decade, said Wombell, lent his work a greater depth.

Hunter agrees with Wombell’s analysis on two counts. First, his work is undoubtedly local, an attempt to “think global, act local”, as he puts it – having started off by shooting his neighbours, and more than a decade later he is still photographing friends and locals in Hackney.

And second, he concurs with Wombell’s comments about the failed promise of technology – that digital networks would liberate people from tradition and physical location, and help them transcend tribal, religious, racial and economic divisions.

He favours a slower, more traditional approach, shooting mostly with a Wista 4×5 camera and, more recently, a large format pinhole.

“People have got a bit too excited about digital technology, thinking you’ve got to have the latest digital this, that and the other,” he tells me. “But it’s not about the equipment, it’s about capturing the light – you can take pictures on anything. You don’t need to spend £1500 on the latest digital multitasking thing. Going to a church hall and taking maybe three pictures in an hour is [as he has done recently in his Prayer Places series] going back to basics. It’s like slow cooking. I like that methodical way of working, not walking around taking lots and lots of shots.”

London stories

Born in Dorset in 1965, Hunter left school at 15 and spent seven years as a manual labourer, an experience that left him “fucking miserable and depressed”. In 1986 he moved to Hackney in east London and got work as a tree surgeon, which led to an opportunity to go to Puerto Rico for a year with the US Forestry Service.

He took a camera along with him and soon realised he had an aptitude for photography, so when he got back he enrolled in an A-Level evening class, which in turn led to a place on a course at the London College of Printing. He graduated in 1994 with a first-class honours degree.

He’d begun making pictures of his friends and neighbours living in squats in Ellingfort Road, titling his work (which included a 3D model on the street) The Ghetto in reference to an article in the Hackney Gazette, which described the area as “a crime-ridden, derelict ghetto, a cancer – a blot on the landscape”.

“I had got very sick of seeing people I knew, travellers and squatters, presented in the media in black-and-white images with captions saying, ‘These people are scum’. I was saying, ‘We’re not scum, we’re just people like anyone else and we need to be shown’. Even though I lived in a squat, I never thought I was outside of society. I always felt I was part of this country and that my voice should be heard. I thought by using colour and by using certain ways of depicting people I could create more empathy.”

The work was shown at the Museum of London in 1995, but his real breakthrough came with a single picture taken from a new series he worked on while studying for an MA at the Royal College of Art. A portrait of a young mother, it closely referenced Jan Vermeer’s 17th century painting, A Girl Reading a Letter by an Open Window, except that his subject was reading an eviction notice from the council, and instead of the bowl of fruit in the original picture, a baby lies on the bed in the foreground.

Taken from his Persons Unknown series (that’s a later project), Woman Reading a Possession Order won the John Kobal Photographic Portrait Award in 1998, and a year later was shown in a group show at The Saatchi Gallery titled Neurotic Realism.

Hunter followed up with Life and Death in Hackney in 2000, another series that drew on painterly references to depict life in the London borough, and then Living in Hell and Other Stories, which used lurid headlines from the Hackney Gazette (such as “Gang Rape Ordeal”) to re-stage scenes from art history.

Unheralded Stories, which was on show at Purdy Hicks Gallery (24 November to 23 December) references great tableaux painters to relate stories from the social history of Hackney.

In Anchor and Hope [pictured], for example, a woman crawls through long grass, evoking Andrew Wyeth’s painting, Christina’s World. In Hunter’s image she’s looking towards an Upper Clapton council estate, the scene of fierce fighting when bailiffs and the police tried to evict all the residents. “It’s nice to be in your own backyard, rather than being the great white explorer,” Hunter says. “Anthropologists going off to deepest darkest Africa to see other cultures don’t realise what’s going on on their own doorstep.”

Fact and fiction

Hunter’s art historical references are designed to lend gravity to the people and scenes he depicts. Some people will get the references, others will only vaguely be aware of a certain dignity, he says, but either way, the aesthetics help ensure the scenes stay in the public consciousness.

“Newspaper headlines come and go. I want to show that they are very serious and that what goes on around you is very important,” he says. “I wanted to make them monumental, and put them in The National Gallery [which commissioned Living in Hell; the first time it had asked a photographer to make a body of work, exhibiting it in 2006]. There is an argument that aesthetics creates a barrier; I’m arguing it takes the barrier down and helps you engage more.

“In school you’re taught this is how you paint, these are the painters who are considered important, this is how you make a beautiful image – even if you reject it, it’s burnt into your skull. So, if some kid sees one of my pictures he goes, ‘Oh yes, that’s a beautiful picture’ and makes a connection, he might start to explore and look into art history and realise that my image is connected back to a long history of representation. Or he might not, but either way I think we do understand that relationship to beauty.”

For Hunter the medium is part of the message, and he’s happy to use elements of fiction in his work, at the very least posing his subjects, and at most staging the whole scene. He describes his early work as propaganda, an active attempt to pit one version of events against another, but argues that his fictions aren’t necessarily less truthful than straight documentary. Living in Hell is a nightmarish series of staged scenes, but it recreates real-life stories, and it documents the mental images summoned up by paranoid newspaper headlines.

“Newspaper stories are historical narratives of our time,” says Hunter. “I’d go to friends’ places and they’d say, ‘I can’t read the Hackney Gazette any more, it’s just too scary – I think I’m going to be raped or murdered’. When you hear about someone being shot on a cold winter’s night, you imagine a horrible scene. And maybe you relate it to TV or cinema or books or Greek mythology – it’s not just a story in isolation; you relate it to the culture around you.”

He favours photography because it has “its feet in reality”, he says, where painting is always an abstraction. All his work is taken on location, so no matter how staged some of the elements are, they retain an historical veracity.

The girl reading the eviction order was reading a real eviction order, for example, and she really was living in a squat. “I look at that image as a historical document,” says Hunter. “Photography does that, it captures objects from a certain time, and that’s what I love about it. You can slightly alter the scene, you can bring in a fiction in a way, but underlying it the core foundations are reality.”

Out of the ghetto

It is the little details that surprise him now, he says – he hadn’t realised how poor some of his subjects looked, or noticed the damp patches on their walls. And his own status has shifted over time too.

When he was living on Ellingfort Road he felt hounded by Hackney Council: now he’s a celebrated member of the community and the council commissions him to create work.

The 3D model of Ellingfort Road is on permanent display in the Museum of London, as are two photographs from Living in Hell at the National Gallery. He can see the irony but doesn’t have a problem with it – he’s just happy to become a mouthpiece for those whose stories he’s telling, particularly when, as an art photographer, he could have ended up with a very small audience.

“There are advantages and disadvantages to every way of getting your work out there, and the great advantage of the art world, and why I started getting involved with it, is you have a lot more control,” he says.

“You don’t get someone editing your pictures, and you don’t become an illustration for someone else’s idea [as you can in magazines and newspapers]. When you love photography as much as I do, you want to have control over how it’s printed, and suddenly in the 1990s we had the opportunity to produce beautiful prints, put them in a beautiful frame and put them on the wall.

“But there are downsides to everything, and the downside of the art world can be that suddenly you’re producing a commodity, and your work is being bought by rich people and shown quite exclusively to them. For me, it’s been really important to go beyond just a small West End gallery where I will only communicate with a few people. I didn’t want to become ghettoised in the art world – if I was just trying to create beautiful objects that would be fine, but I’m trying to put across a message as well.”

More than three-quarters of a million people saw the show at the National Gallery and, of that, the majority were school groups. “I looked at the demography quite closely, and those groups weren’t middle class, they were people who didn’t want to go in the first place,” laughs Hunter.

This status also now affords Hunter more control when his photography is shown in newspapers and magazines. When his work is shown in The Guardian, he says, the text that goes with it discusses his ideas, not someone else’s.

And he’s continuing to work with local papers, recently completing a project for Hackney Today, for example, a council-run publication delivered to every household in the borough.

To return to Wombell’s argument, he aims to act locally then get the message out to as many people as possible. “I want to talk to everyone,” he says, “so that the same mistakes aren’t repeated.”

BJP – Author: Diane Smyth