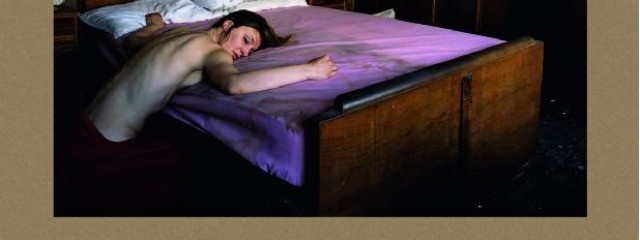

Tom Hunter ‘The Way Home’, 2012.

In this book I have set out many bodies of work that I have created over the last twenty-five years, whilst making my journey through the streets of Hackney, trying to make sense of this urban maze and find my way home. It seems strange now to think back to a time of sitting in the pub in Blandford, Dorset with my mate Fred and discussing our nights itinerary of catching the tube to Soho, going to the 100 club, seeing some bands and ending the night at the Ritz. All a complete fantasy, funny, but, as the bell rang for last orders at 10.30pm, scary to think this pub on a wintery Tuesday night, with just the two of us at the bar, might be the limit of our horizons. A few months later and my girlfriend at the time is accepted at the London College of Furniture, it’s my big chance to escape and soon after I move to Hackney. I’ve made it to London but there’s no tube in Hackney, no 100 club and no Ritz, its Tuesday night on Lower Clapton road and just me and a local, who won’t give the time of day, in the Fountain pub. On the way home, I look in the once grand White Hart and into an unfamiliar landscape of ragga, dancehall and Jamaican heavy bass, it’s another world. Later I walk past the Mothers Hospital, closed but now squatted, the facade of the hospital makes a statement of intent by the founders, the Salvation Army, a progressive imposing building built for the people of the East End but now abandoned. Hackney is littered with veneers of a bygone era of grandeur and statements, interwoven with people washed ashore, mixing up cultures and architecture, creating worlds within worlds, showing glimpses of a life I never imagined whilst planting trees for the Forestry Commission in Dorset. But my connection with Hackney was born, as if I was one of the 123,909 live births recorded at the Mother’s hospital, and a life’s journey started.

It is this mixing of cultures, architectures, people and histories that has so captivated me and held me in the arms of Hackney. Every building has a thousand tales to tell and in this book I’ve tried to tell a few. Whilst my subject has always been Hackney the influences behind my art practice are found in the work of Johannes Vermeer, the Pre-Raphaelites and latterly a whole raft of art historical paintings. This came as a complete surprise to me as a young upstart striving for social justice in a squat in Hackney. While looking for a radical approach to my art I found revolutionary artists in the most traditional of art forms.

I first came across the work of Johannes Vermeer in the library at the London College of Printing whilst doing my photography degree back in 1994. I had just finished my degree show ‘The Ghetto,’ a 3D model and series of photographs of a squatted street in Hackney, which was home to myself and around 100 others. At the time we were trying to save the street from demolition and my eviction from taking me into another class of homelessness from that of squatter. In the making of this work I began taking photographs on a large format camera, which produced 5 inch by 4-inch transparencies. These transparencies changed my whole notion of photography. On collection of these small windows and their placement onto the light box I was completely transfixed, as if I were a peasant from the dark and distant past transported from the fields of rural England and into a cathedral, to be mesmerised by the stained glass windows with the sunlight pouring through these heavenly portals. Colour and light became key to the way I looked at my neighbourhood, seducing me and taking me into a kind of meditation about my life, my way of living and the culture that surrounded me. Once these transparencies were installed in the model, which was lit from within, my whole street became a kind of cathedral to our neighbourhood, where I could meditate upon my life.

Showing this work to my tutors for the first time gave them thought for me to look back at the work of the golden age of Dutch painting, which drew so strongly on light and colour. At this point I was an incredibly keen student aged 29. I had left school at 15 with one CSE and was not considered capable of taking O levels, so I went to work on farms and building sites, for the Forestry Commission and eventually as a tree pruner in Regents Park. I went straight to the library to investigate the golden age of Dutch painting. After a number of books I came to Vermeer and it all clicked into place. I was transfixed by his use of light and colour and taken again into that magical state of meditation. As I read into the artist the more I became intrigued and inspired by his life and his practice as an artist.

This could have been the end to this fleeting insight into another artist’s life and his practice. I wrote my appraisal of my degree show and quoted the golden age of Dutch painting as an influence and the paper was consigned to the filing system of a squatted abandoned house in East London. My life took another turn and I set out on a double-decker bus to Europe to put on free parties and festivals and revel in the chaos of techno music and open roads. I had an intense couple of years living on my wits as part of a travelling convoy of purveyors of alternative culture, preaching the doctrine of free parties, no rules and a life of self-regulation. But a call from Hackney beckoned me back to London and the Royal College of Art, so on selling the double decker to a Welsh punk band, ‘2000 Dirty Squatters’ in a disused warehouse in Berlin, I set off in an overladen and limping estate car. I returned to my long term squatting neighbourhood of Hackney to resume my residency in Ellingfort road. Soon after my education began at the RCA myself and my neighbours once again became the recipients of legal notices from the High Court of Justice addressing “Persons Unknown in the matter of land and premises from The Mayor and Burgesses of the London Borough of Hackney in order to recover said land and premises.” Again I took this as a challenge to our culture and lifestyle and set out to produce work that might raise the status of our fight with the local authorities and I returned to the work of Vermeer.

One of my attractions to photography is its implicit relationship to realism, a medium deeply rooted in its indexical nature to a notion of reality. Vermeer gave us a window into a real world but also a world imagined through his art. Other elements of his work I found fascinating were his relationships to such a small community, his local world. His work takes place in Delft, a small town in the Netherlands, and within this small world he looks even closer, as if under a microscope, at a few people that make up his world, a world of intimate scenes of small groups and individuals. Focusing in on such small details and illuminating its subjects in such a devoted way, really lifts the status of the sitters. So for me Vermeer was a painter of the people, a revolutionary artist in his practice. His use of realism and his social commentary lifted the ordinary people to a higher status within their time and forever more. This is how I wanted to present my friends, neighbours, lovers and myself to the world, as a meditation on life. From this understanding of subject I composed and rendered my photographic series of works ‘Persons Unknown.’

One of this series ‘Woman Reading A Possession Order’ took as its starting point, Vermeer’s ‘A girl reading a letter at an open window.’ This depicts a quiet moment when a woman reads a letter at an open window bathed in soft northern European sunlight. We’ll never know what is in the letter but it could be a love letter from a fiancé fighting for his country in a war of independence against the oppressive rule of the colonial powers of Spain. So the work talks of the struggle of the ordinary people of Delft and their battles, not explicitly showing the battlefield or the carnage of war but one woman’s meditation on life and her situation, shown with dignity, subtlety and beauty. Likewise my reworking shows a girl reading her eviction order. The subject is given space, dignity, light and beauty to tell her own story in its own time. The girl in the photograph was talking about her very personal moment of struggle with eviction, which can be read as a universal moment, where we could all identify with the subject and her suffering.

Since Vermeer I have taken many influences from art historical paintings and the lives of the artists, investigating how these figures have recorded, described and given narratives to their environments, lives and subjects. I have not been interested in trying to replicate the art from a historical context but rather reinvestigate, understand and reinterpret what has happened before. This works for me as an artist in contextualising my work, giving it multiple layers and asking the classical and contemporary viewer alike to question art in its relationship to society. My fascination with the Pre-Raphaelite brotherhood started at a young age with a picture postcard of ‘Ophelia’ on my sister’s bedroom wall. This took pride of place amongst many artworks until she attended an art foundation course in Bournemouth and quickly learnt how uncool they were. The image was subsequently relegated to the bin. Although it is the most popular image from the Tate collection and is viewed more than any other painting in their collection, it is still given a somewhat diminished place in the history of art. By taking on some of the attributes associated with the Pre-Raphaelite artists, such as social engagement, which has been largely erased from the cultural understanding of this group, and the obvious intertwining of beauty and nature I could again reinvestigate my much maligned inner city landscape and society.

In my series ‘Life and Death in Hackney’ these strands of practice enabled me to paint a landscape, creating a melancholic beauty out of the post-industrial decay where the wild buddleia and sub-cultural inhabitants took root and bloomed. This maligned and somewhat abandoned area had become the epicentre of the new warehouse rave scene of the early 90’s. During this time these old print factories, warehouses and workshops became the playground of a disenchanted generation, taking the DIY culture from the free festival scene and adapting it to the urban wastelands. This Venice of the East End, with its canals, rivers and waterways, made a labyrinth of pleasure gardens and pavilions in which thousands of explorers travelled through a heady mixture of music and drug induced trances. By creating my reworking of John Millais’s ‘Ophelia’ I drew on all these influences combining the beauty and the degradation with an everyday tale of abandonment and loss to music and hedonism. This image shows a young girl whose journey home from one such rave was curtailed by falling into the canal and losing herself to the dark slippery, industrial motorway of a bygone era. The rave scene that grew out of the industrial rubble subsequently went back out into the world and into the festival scene, which had sown its seeds originally, taking the raves back to the shires and across Europe.

This connection with the urban and the rural has always played a big part in my work, bringing my village perspective to the city. But it was my city view of the countryside that was challenged on a return visit to my native Dorset and gave me the initial inspiration for ‘Living in Hell and Other Stories’. Whilst spending an afternoon by the River Piddle at Moreton I came across an article that described a local doctor who had been forging prescriptions to feed his wife’s drug addiction. The doctor was a family friend and the contradiction of society’s problems being uncovered in the rural idyll of Dorset came as a shock after spending so much time in Hackney. The article went on to talk about Thomas Hardy, my local Dorset hero and guiding star, and how he had found all the ingredients for his novels in the grim news articles of the Dorset County Chronicle. From my first days in Hackney I have been an avid reader of the Hackney Gazette, looking for jumble sales and scaring myself with the stories of Hackney’s underbelly. After years of collecting these stories, in a dusty pile in the corner of my living room, I revisited them. The headlines jumped out at me; ‘Halloween Horror,’ describing a trick or treat mugging on a woman’s doorstep, ‘Gangland Execution,’ the story of a body discovered by boys playing by the River Lea and ‘Living in Hell,’ the report of an elderly lady abandoned by her family, the council and society, left to rot on an cockroach infested sofa, the order of civilisation crumbling away as the fingers of Hell eat though the wallpaper and into the home. How could this be happening in one of the richest cities in the world? From this I created ‘Living in Hell and Other Stories,’ my National Gallery show of 2006, where I wove headlines from the Hackney Gazette into contemporary images referencing paintings in the National Gallery collection. ‘Living in Hell’ references the scene of rural French poverty depicted by the Le Nain brothers, showing an impoverished old peasant women. In the National Gallery she has her family and pride but in Hackney she has nothing but the cockroaches.

The focus of my work took a different turn after this and rather than the media stories of the Gazette my interest turned to more personal tales and I decided to focus on the more poetic and less literal representations of life in Hackney. ‘Unheralded Stories’ looked at the folklore and myths that have built up around my community and surroundings over the years. This series was much more engaged with the epic landscape of Hackney, creating large historical tableaus of significant but unchampioned tales of life in Hackney. ‘The Mole Man’ from this series is a requiem to Hackney’s infamous patron saint, the man who spent years burrowing beneath his house until his forced eviction by Hackney council. This is his journey’s end in the subterranean underworld of Hades and it shows the ‘mole man’ laid out in a hell of his own making. I met him several times and was once invited to view his kingdom. The subterranean world he created caused buses to change their routes in case they were dragged down beneath the tarmac, just as Odysseus’ fleet of ships was pulled under the waves by Poseidon after his conquest of Troy. In this series I wanted to investigate the notions of depicting suffering through beauty and the way that the artist creates exoticism from the unknown. I wanted to draw on these themes as I had from the artists at different times in creating my own world-view within Hackney. I took as inspiration great artists such as Théodore Géricault and his ‘The Raft of Medusa’ and Eugène Delacroix’s ‘The Death of Saradanopalus.’ ‘The Raft of Medusa’ inspired ‘Hackney Cut’ and describes the sinking of a French passenger ship leaving a small group of survivors on a raft. This painting struck a chord within my art practice in the way that Géricault was attacked by the art critics of his time for using painting to depict such a desperate topic for his own artistic endeavours. I have always been fascinated by this critique of art, in that sensitive or troubling issues should not be depicted in terms of beauty, but how else can an audience engage with such subject matters with understanding and sensitivity? It is Hardy’s beautiful writing of eighteenth century rural poverty which gives me understanding of the people, Picasso’s beautiful painting of ‘Guernica’ and its description of Hitler’s use of the Blitzkrieg which moves me to tears and Francis Ford Coppola’s use of colour, light and beauty in ‘Apocalypse Now’ which for me makes sense of the complete futility and madness of war, not black and white textbooks. The notion of the exotic is represented by Delacroix in ‘The Death of Saradanopalus’ by depicting the Orient as something almost otherworldly, beautiful, menacing and mysterious. But in my ‘The Death of Colotti,’ rather than travelling to far away lands to find the unknown and to create the exotic I found this beauty on Graham Road, in an old Italian café established in the 1930’s to bring ice cream, pasta and coffee to the hungry workers of Hackney. When the grandmother died the flat above the shop, for a brief moment in time, became a shrine to the Italian Catholic maternal culture. Just as Delacroix’s Orient and traditions were never understood but reinvented for the West’s palette, the Italian café reinvented its culture for the English tastes and served chips with everything. The cultures and tastes of Hackney are constantly mixing and changing and now the beautiful café has been sold and the kebab bar has moved in.

As Thomas Hardy was derided to the point of persecution by his critics for his last novel ‘Jude the Obscure’, I also felt the strain of representing people when it was put under such a huge spotlight in the National Gallery show. As with Hardy, who gave up the genre of the novel to take up poetry, I too chose to shift the focus of the nature of my work on to the landscape that constitutes my neighbourhood. This now forms the underlying map to my photography. But it started with a ramble to the Forty Foot with Leopold Bloom, it was there that I met my mother, “A great sweet mother? The snot green sea. The scrotum tightening sea… Our mighty mother!” (James Joyce, Ulysses). During my three-month stay in Dublin I found refuge from Hackney and its people and solace in the Victorian bathing places and the freezing March waters of the Irish Sea. Whilst taking my ablutions every morning I really did find my scrotum tightening and the air punched out of my lungs, as if by Poseidon himself. After each baptism of ice I set out to portray the sweet mother and the womb-like seas of Dublin Bay in my ‘Dublin Bay’ series. The camera that distilled the soft Irish light was a large format pinhole camera made for me by my great tutor at LCP, Paul Smith. This gave me the inspiration and fortitude to return to Hackney and continue with my life’s work.

On my return I again set out across the urban landscape on my bicycle on Sunday mornings, listening out for that haunting, repetitive bass bin hammering that used to drift across the canals and waterways of Hackney Wick. But now the bass bins had been evicted and the evangelical voices of worshippers rose above the ever-present A12 traffic trundle. So instead of the meditative waters of Dublin Bay I immersed myself in the old and new ‘Prayer Places.’ This began by visiting the synagogues, mosques, churches, chapels and temples of Hackney. I set up my camera centrally in these spaces, taking my glove away from the pinhole and leaving the atmosphere to filter through over fifteen to thirty minutes. This practice allowed me to work both peacefully and meditatively in a respectful and unintrusive manner, where the image is not grabbed, not flashed and not audible. In some way the camera becomes like a Buddhist prayer wheel, slowly and silently making its mantra. It also enabled me to talk and engage with the priests, imams, rabbis, apostles and clergy. On one such visit to the mosque on Shacklewell Lane, the Turkish imam pointed out a plaque on the entrance wall. It reveals that the mosque was originally built as a synagogue for the local Jewish community with the help of Charles Rothschild. The layers of people and cultures are so thin, it takes almost nothing to peek though to another world, another age, as if wormholes are all around us.

Over the years I have travelled with my camera and bicycle all over the East End, recording and rendering the very fabric that makes up the community and spirit of the area. It has taken me to the structures and institutions where the theatre of life is acted out as if on a stage set, from the sparse 60’s council estate community halls to the richly decorated Hackney Empire and the Drapers’ hall, centres of culture and trade. Indeed all these theatres signpost my journey, leading me to imagine the brass bands, school plays and the Punch and Judy shows that initially sparked my imagination at the country fairs and beaches of Dorset. This journey has led me back in a complete circle, to my first black and white images where, as an immigrant from Dorset, I first set up shop on the streets of Brick Lane, selling my wares procured from jumble sales the previous day and snatching images on my 35mm camera of surprised customers. So although my practice, from the hunter to the absorber, has changed the themes of place and identity remain the same. The later pinhole images taken on ‘Ridley Road Market’ peel back the layers of the waves of immigrants that have arrived in Hackney over the generations, setting up shop and bringing their cultures to sell and share their food and tastes and opening our palettes and eyes to new worlds. Although there are no people portrayed, the sense of culture and place resonate throughout the images. All these public spaces where communities come together to relax, share, discuss, argue, pray and trade join up the dots between my series’ of photographs portraying Hackney’s people and issues, framing the works and putting them into the social, political and architectural context of my surroundings.

In Hackney I have found a place, which accepts its incomers as a part of life that refreshes the palette and adds to the layers of its history. Like Vermeer I have concentrated on my local area and in this book I’ve tried to show my journey home to where I live. Although I have not repeated directly referencing Vermeer in my work since ‘Persons Unknown’ I have always tried to keep his art practice at the core of all my work. Whether I’m taking photographs of the residents of condemned tower blocks, shopkeepers, barmaids or the disenfranchised this way of working has shaped nearly every photograph I have ever taken since this time. Vermeer may have never left letters or great text regarding his reasons and the methodology of his artwork, but his paintings stand as a testament to a profound understanding of the universality, that connects every one of us as human beings together by small every day things. For me he has created a template for artists wanting to show the dignity of the ordinary people involved in their daily lives, lifting the ordinary into the extraordinary. His work stands as a testament to a honourable tradition of equality and social justice through attention to detail and a rendition of beauty in the ordinary. This idea remains with me, lets try to lift the people in our art whatever the art form and however the people. I hope this book goes in some way to achieve this.